The distinction between the Absolute and the Infinite expresses the two fundamental aspects of the Real, that of essentiality and that of potentiality; this is the highest principial prefiguration of the masculine and feminine poles.

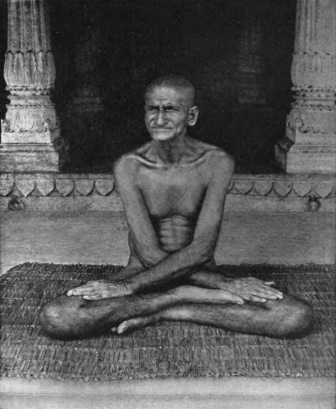

Frithjof Schuon

Schuon sees in the human body a “message of ascending and unitive verticality […]; in rigorous, transcendent, objective, abstract, rational and mathematical mode” in man, “and in gentle, immanent, concrete, emotional and musical mode” in woman [1]. As Patrick Laude points out, feminine beauty “plays a preponderant role in the spiritual alchemy that issues from the oeuvre and spiritual personality of Schuon, […] in no way foreign to the highest expressions of gnostic Sufism”, as evidenced by “Ibn Arabī and Rūzbehān among many others” [2].

Summarizing Schuon, Timothy Scott reminds us that nudity represents the norm — primordial man was naked, “primitive” peoples are also naked — and that it “symbolizes quintessential esoterism […], the Truth unveiled”, the ordinary garment then representing exoterism [3]. In his biography of Schuon, after noting the convergences of views that unite Schuon, Rūzbehān, Omar Khayyam, and Henri Corbin regarding the spiritual significance of nudity, Jean-Baptiste Aymard quotes this excerpt from a letter by Schuon:

“Given the spiritual degeneration of humanity, the highest possible degree of beauty, which belongs to the human body, could not play a part in ordinary piety; however this theophany may be a support in esoteric spirituality, and this is shown in the sacred art of the Hindus and the Buddhists. Nakedness signifies inwardness, essentiality, primordiality and consequently universality […]; the body is the form of the Essence and thus the essence of form” [4].

In a published passage from his largely unpublished Memoirs, Schuon remarks “how contemptible is the neo-pagan and atheistic cult of the body and of nudity. What is in itself noble in nature is good for us only in its function as a support for the supernatural; cultivated apart from God, it readily loses its nobility and becomes a humiliating fatuity, as the stupidity and ugliness of worldly nudism precisely prove” [5].

In an interview published in 1996 by the American magazine The Quest: Philosophy, Science, Religion, The Arts, Schuon develops the sacredness of nudity:

“In an altogether general way, nudity expresses — and virtually actualizes — a return to the essence, the origin, the archetype, thus to the celestial state: ‘And it is for this that, naked, I dance’, as Lallā Yogishvarī, the great Kashmiri saint, said after having found the Divine Self in her heart. To be sure, in nudity there is a de facto ambiguity because of the passional nature of man; but there is not only the passional nature, there is also the gift of contemplativity, which can neutralize this, as is precisely the case with ‘sacred nudity’. Thus there is not only the seduction of appearances, there is also the metaphysical transparency of phenomena which permits us to perceive the archetypal essence through the sensory experience. When the saintly bishop Nonnos beheld St. Pelagia entering the baptismal pool naked, he praised God that He had not put into human beauty just a cause of downfall, but also an opportunity for elevation towards God.” [6]

[Adapted from the Wikipedia entry on Schuon.]

Notes

[1] Frithjof Schuon, From the Divine to the Human, World Wisdom, 1982, p. 85.

[2] Patrick Laude, Frithjof Schuon: Life and Teachings, SUNY, 2002, p. 123.

[3] Timothy Scott, ““Made in the Image”: Schuon’s theomorphic anthropology” in Sacred Web Journal, Vol. 20, 2007, pp. 216, 219.

[4] Jean-Baptiste Aymard, Frithjof Schuon: Life and Teachings, SUNY, 2002, pp. 73-74

[5] Frithjof Schuon, Par “l’amour qui meut le soleil et les autres étoiles”, Hozhoni, 2018, pp. 102-103

[6] Quest Magazine, Vol. 9, No. 2, Summer 1996, p. 78